By David McCormick

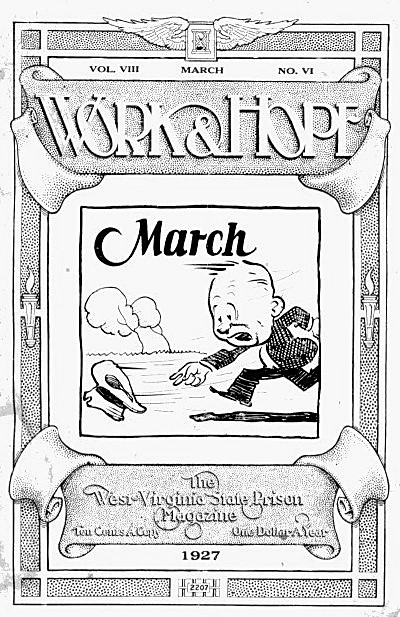

“Let ‘Work and Hope’ be the voice of the men inside speaking to those on the outside, and may many people hear it.” These words spoken by West Virginian John Cornwell were carried in the January 1, 1920 edition of the Independent-Herald (Hinton, West Virginia). Cornwell, optimistic about the success of the prison publication, paid the fee of $1.00 for a yearly subscription to the prison publication. Cornwell held high hopes that the nascent publication would draw more interest in the state’s prison system, thus reversing the mantra—how little money can we expend in funding the state’s institutions to call for an increase in funding. This monthly magazine was published at the West Virginia State Penitentiary starting in October of 1919.

The pages of the June 1921 edition of the prison digest opened on another hopeful note. In a letter to the magazine penned by West Virginia’s newly elected Governor, Ephraim Franklin Morgan, floated the idea of making the penitentiary at Moundsville a model institution. Also in this issue was a short discourse by Judge Wedhams of New York, defending his position on the number of paroles granted from the bench. Apparently, people felt they were too lightly conveyed, a position he did not agree with. And Adolph Lewisohn, a successful New York businessman and philanthropist, expressed his pro stance on prison reform. These last two items were taken from larger newspapers.

Work & Hope was first published in October 1919 at the West Virginia State Penitentiary located in Moundsville, Marshall County. Within the pages of the prison periodical were original articles, drawings, poems, and short stories. To offer a glimpse of life throughout the Country, reprints of articles were selected from national newspapers to run in the pages of this prison publication. The magazine was looked upon as the “first attempt at vocational training in the West Virginia Penitentiary,” and in that vein, most of the original offerings were penned by inmates.

The writing in the publication tended to be upbeat for the most part. Issues covered holidays such as Christmas, Fourth of July, Mother’s Day, and New Year’s Day. Staff editorials were humorously referred to as “penatorials.” Much of the writing uses humor in discussing prison issues. That is the main theme in a column from “Erf McGerf,” who writes in a faux hillbilly dialect when discussing serious issues. Following this line of humor, one of the magazine’s columns titled ‘Laughs’ a prison poet reported tongue in cheek on what the prisoners were thankful for on Thanksgiving in 1926. The message strikes a humorous tone with the following: “We are thankful that we didn’t get life or have to live in Florida.” Could the wordsmith have been referencing the cooler clime of West Virginia versus the hot humid weather in the ‘Sunshine’ state? This was followed with, “We are thankful we are not ‘Peaches husband.’” This message insinuates that ‘Peaches’ may not be the loyal wife back home pining for her incarcerated spouse. Another humorous entry, “We are thankful that the judge who sentenced us did not take from us the privilege of being thankful.” But the humor ends there with the following soulful refrain, “I laugh.” “That I may not weep.” Editorials took a more serious tone when discussing politics, or legislation regarding the prison population, and events going on within the prison itself

As with any new publication, Work & Hope underwent growing pains in trying to find its footing. The first issues of the publication were produced by hand. An effort that proved very tedious and time-consuming. Work & Hope’s inaugural issues were twelve pages in length that soon expanded four-fold before finding its level at thirty-two pages. This prison tome was marketed as “THE PRISONER’S ONLY VOICE TO YOU.” Ten cents would buy a single copy. Buying a yearly subscription was the better value at one dollar. Inmates received a twenty-five percent discount.

In spite of Governor Cornwell’s optimistic view of Work & Hope, the publication’s editors had to walk a fine line, as prison officials had the final word on its content. They had to put on the best face possible when discussing anything negative. For example, an article in a 1927 issue titled “Ball and Chain Gone” really dredged up past torturous punishments in gory detail. In years past the prisoners actually did wear a ball and chain, and were under heavy guard when working outside the prison. But in 1927 no more ball and chain or heavy guard when toiling outside the prison walls. In speaking of the “old days,” the prisoner goes to a darker place when describing men being flogged with a two-inch wide strip of leather-harness soaked in water overnight, and then dipped in sand. This whipping caused welts and drew blood from the prisoner’s backs. The article confides that some prisoners were “beaten to death or otherwise slaughtered” behind the prison walls. Other punishments were also described in detail. This narrative was allowed to go to print. Most likely, the present prison administration wanted to publicize its more benign prison management practices. Surely this narrative about past prison bloodletting would not have passed muster with the prison administration from the “old days.” With this better treatment, the magazine staff had no qualms in doing their part in touting the prison’s progressive reform in ceasing the implantation of what they referred to as the ‘torture laws’.

The Work & Hope staff usually knew where the line was drawn. In one editorial the magazine acknowledged that, “Of course, it should not be expected that a prison magazine tells all that occurs in prison, there are obvious reasons why this could not be done.” This caveat was because the prison administration controlled what was allowed to fill the pages and what was not.

Redemption was addressed in a number of the magazine issues, such as the October 1929 issue that told of Dorothy M. Brown a leading champion of the poor. Another short piece in the same issue told of the Organization of the Pathfinders of America touting the redemptive tenets of their message that were highlighted in letters from prisoners around the Country. A 1924 piece in Work & Hope told a tale of the deliverance of one prisoner who had served upwards of two decades. The editors made use of two photographs of the former inmate to highlight the message. The first picture labeled “the old” showed a man with a haunted demeanor, whereas the picture of him after several years out of prison is dubbed “the new.” This photo depicts a fine-looking uplifting individual. The moral is it cost thousands of dollars to keep him behind bars, but given a fair chance at parole, he became a trustworthy citizen after release.

In spite of the seemingly rosy pictures described in many of the publication’s articles, violence and injustice were regular occurrences. In the monthly “Day by Day” section of Work & Hope, one can find events that take place within the prison; The PEN Revue, a vaudeville performance put on each year by the prison band. Mention is also made of the gospel choir and sports activities. Violence is also a subject covered in “Day to Day,” but not how one would expect. The cases of violence discussed in the prison publication were not only those that applied to the incarcerated but also the violence visited upon the guards. The Aug. 25, 1926 edition, relates that one guard suffered a serious stab wound while three other guards were also attacked with a knife.

This prison magazine seemed to bring a humanizing effect on the inmates. One article enforces the idea that, even if living in dehumanizing conditions, one could still harbor feelings of fairness, and could decipher right from wrong. In commenting on the George Remus murder case where he was charged with killing his wife. The inmate takes strong issue with Remus’s acquittal on the grounds of his temporary-maniacal insanity. He could not fathom how a jury of Remus’s peers could meet in agreement, that he was sane in the morning, but not in the afternoon when he murdered his wife, and then sane again at the end of the day. He finished by declaring, “There is not in all of American jurisprudence a more disgraceful chapter than the Remus case.” Work & Hope was acclaimed by West Virginia government officials and those who wanted prison reform. But it did not last. The final edition was pulled from the press in September 1931. But what was the reason for its demise? Some mention the huge influx of prisoners, but other penal institutions managed to turn out prisoner-run publications. Some mention the effects of the Great Depression, but the publication was basically self-supporting. Did the focus of prison officials become more law-and-order-minded? Or did everyone just lose interest? What is known is that for a little over a decade, Work & Hope broke new ground that gave meaning to the prisoners through its pages filled with the news of goings on—within the walls, and outside them—with its editorials and humor. But what is most noteworthy is that although the magazine only survived a little over a decade, it recorded a quarter of a century of life within the prison walls, both good and bad.

DAVID McCORMICK

McCormick, David. "Work & Hope: West Virginia Prison Magazine." Goldenseal West Virginia Traditional Life, Summer 2025. https://goldenseal.wvculture.org/work-hope-west-virginia-prison-magazine/