By Danny Kuhn

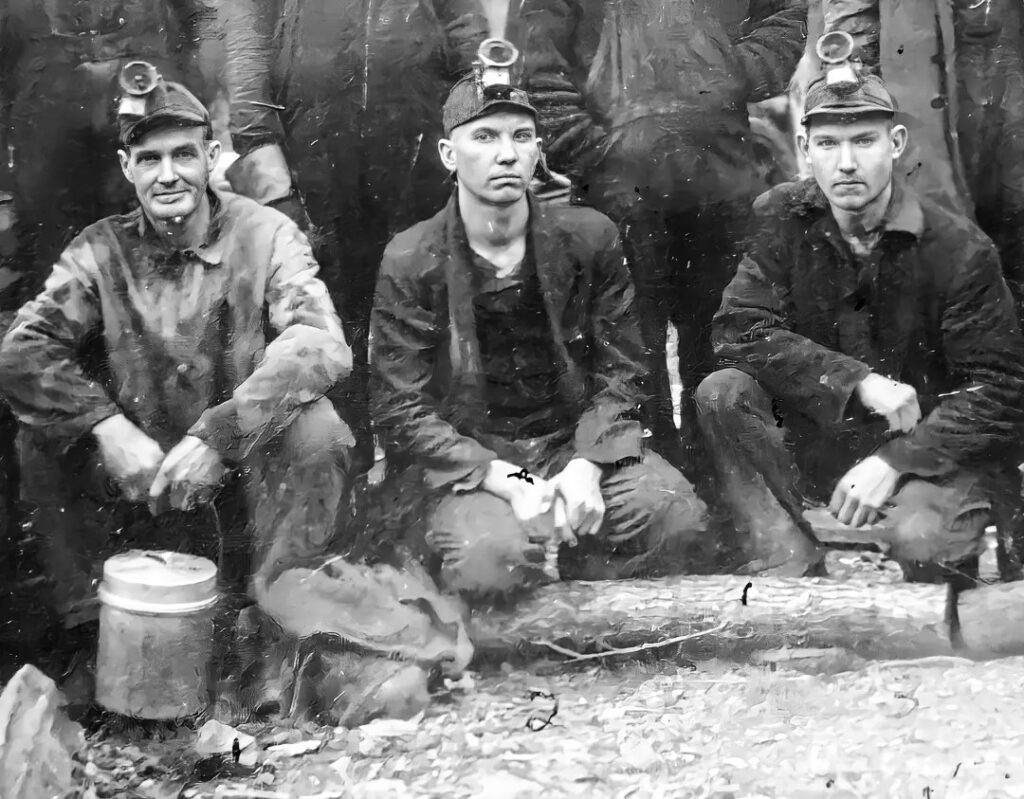

From the first European settlement in what is now West Virginia until a couple generations ago, farming was our most common profession. In the 1880s the railroad opened vast coal reserves ready to fuel America’s industrial revolution, and many farm families lost their land to shady mineral rights deals or moved to the coal camps following the promise—often broken—of a more stable income. My grandfather, Calvin Bennett, went in the opposite direction during World War II, moving his wife, the former Roxie Sheaves, and ten children from Gatewood in the Fayette County coalfields to a 200-acre farm on Adair Ridge in Monroe County.

Having a big family and loading coal for a living did not provide enough money to buy the property outright, of course, so he was taking a considerable leap of faith that he would be able to not only feed everyone from the farm produce, but also make enough extra to pay the mortgage and taxes. This plan left little left over to furnish the substantial 1900s farmhouse, so, the self-sufficient Mountaineer made what was needed from what he had at hand.

The wooded area of the farm was rich in native black walnut, sugar maple, white oak, and eastern red cedar. He sold some of the most valuable timber, particularly the black walnut, to help raise cash. With that money, he built a workshop, stocked it with tools, and taught himself furniture making. Those “made to last” pieces still grace the homes of his various descendants today.

One piece of “store bought” furniture that made the trip from Gatewood was an enormous sleeper sofa purchased from Montgomery Ward in 1922, the year after Calvin and Roxie married. The sofa and accompanying chairs were shipped to the train depot at Sewell, on the opposite side of New River. A ferry operated from the depot to transport freight across the river for a small fee. From there, Calvin hired a buckboard and a team of two mules to haul the furniture up the mountain, where a friend who owned a Model T Ford truck met him and delivered the load to Gatewood. Thus, the sofa and chairs traveled by train, boat, horse and buggy, and truck all in the same day.

“The wooded area of the farm was rich in native black walnut, sugar maple, white oak, and eastern red cedar. He sold some of the most valuable timber, particularly the black walnut, to help raise cash. With that money, he built a workshop, stocked it with tools, and taught himself furniture making.”

This well-loved game table, made by Calvin Bennett, was made using walnut, maple, and cedar.

Today, that century-old sofa and several of Calvin’s handmade pieces have found a home in my West Virginia off-grid summer cabin. Though unbelievably heavy and painfully sagging, the sofa now sometimes seats my Gen Z grandchildren, the fifth generation of what we jokingly call “Bennett Bottoms” to occupy it.

Calvin and Roxie had four more children after moving to Monroe County; in all, they had sixteen, with thirteen living past infancy. They had been married almost 63 years when Calvin died in 1984, peacefully and suddenly while slowly driving along Adair Ridge Road. A neighbor saw his car eased into the ditch, still running. Coming out to offer assistance, the neighbor found Calvin expired, leaning on the steering wheel. We will never forget his determination and resourcefulness. His furniture pieces may lack elegance, but are study and practical, much like the man himself.

DANNY KUHN

(BA Marshall University, MA, West Virginia University)

Kuhn, Danny. "The Furniture Remains." Goldenseal West Virginia Traditional Life, Summer 2025. https://goldenseal.wvculture.org/the-furniture-remains/